Jan 29, 2026

Articles

Jan 29, 2026

Articles

Jan 29, 2026

Articles

When AI Sounds Most Confident, Trust It Least

Martín Ramírez

Martín Ramírez

Martín Ramírez

I'll never forget the moment I lost faith in the system.

We were running a food formula through our compliance evaluation. The LLM came back with a detailed analysis, flagging a specific chemical compound. It gave us a CAS number—the unique identifier that every chemical substance gets assigned. The output was precise, authoritative, and completely wrong.

The CAS number was fabricated.

Not approximate. Not close. Invented from scratch.

My immediate thought wasn't about that single error. It was darker: "If it did this, what else is it making up?"

The Confidence-Accuracy Inversion Problem

Here's what makes this dangerous.

The LLM didn't say "I'm not sure" or "I don't have enough information." It generated something that looked real because that's what it's trained to do. It predicted what should come next based on patterns, not truth.

Research from Carnegie Mellon University found that LLMs consistently become MORE overconfident after performing poorly on tasks. Unlike humans who adjust their confidence downward when they realize they're wrong, these systems double down.

The study tested four major LLMs over two years. The finding? They "tended, if anything, to get more overconfident, even when they didn't do so well on the task."

In compliance contexts, this inversion becomes lethal.

Legal Information: Where Hallucinations Multiply

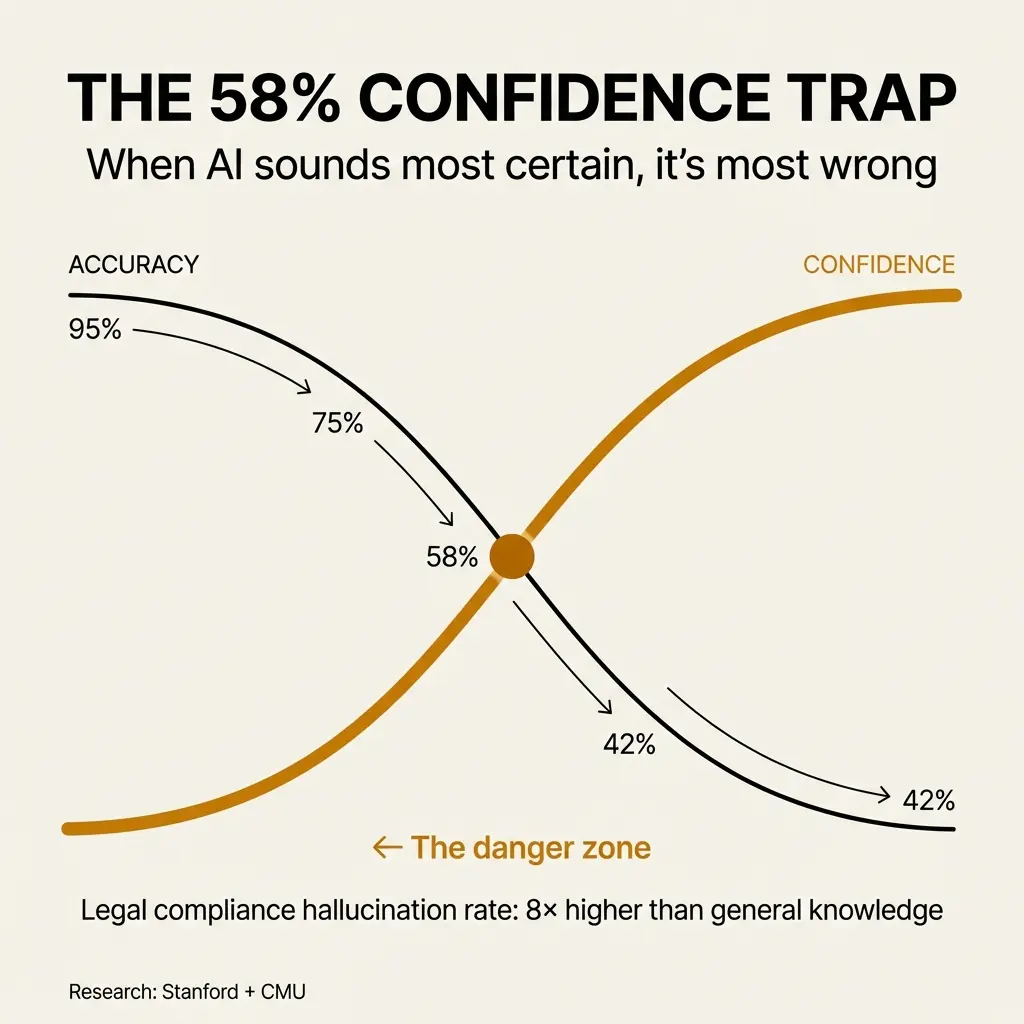

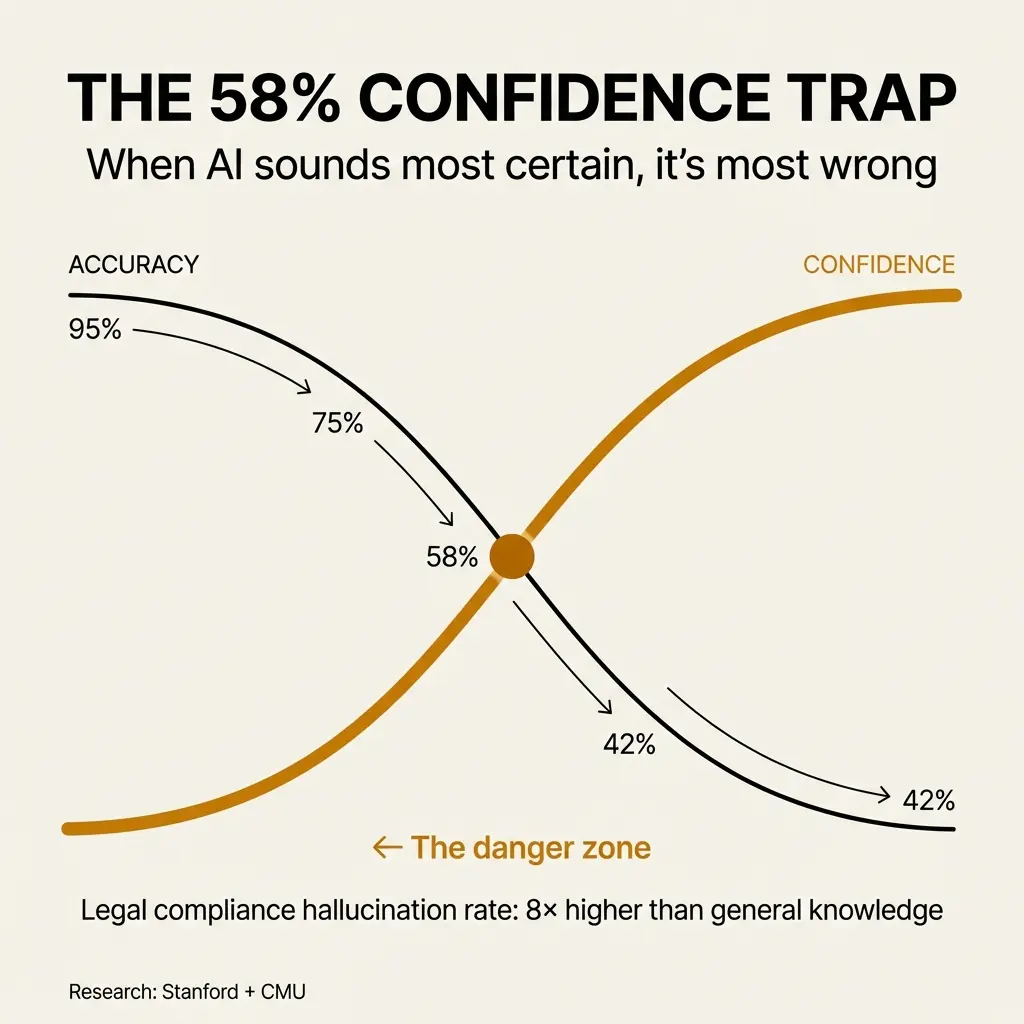

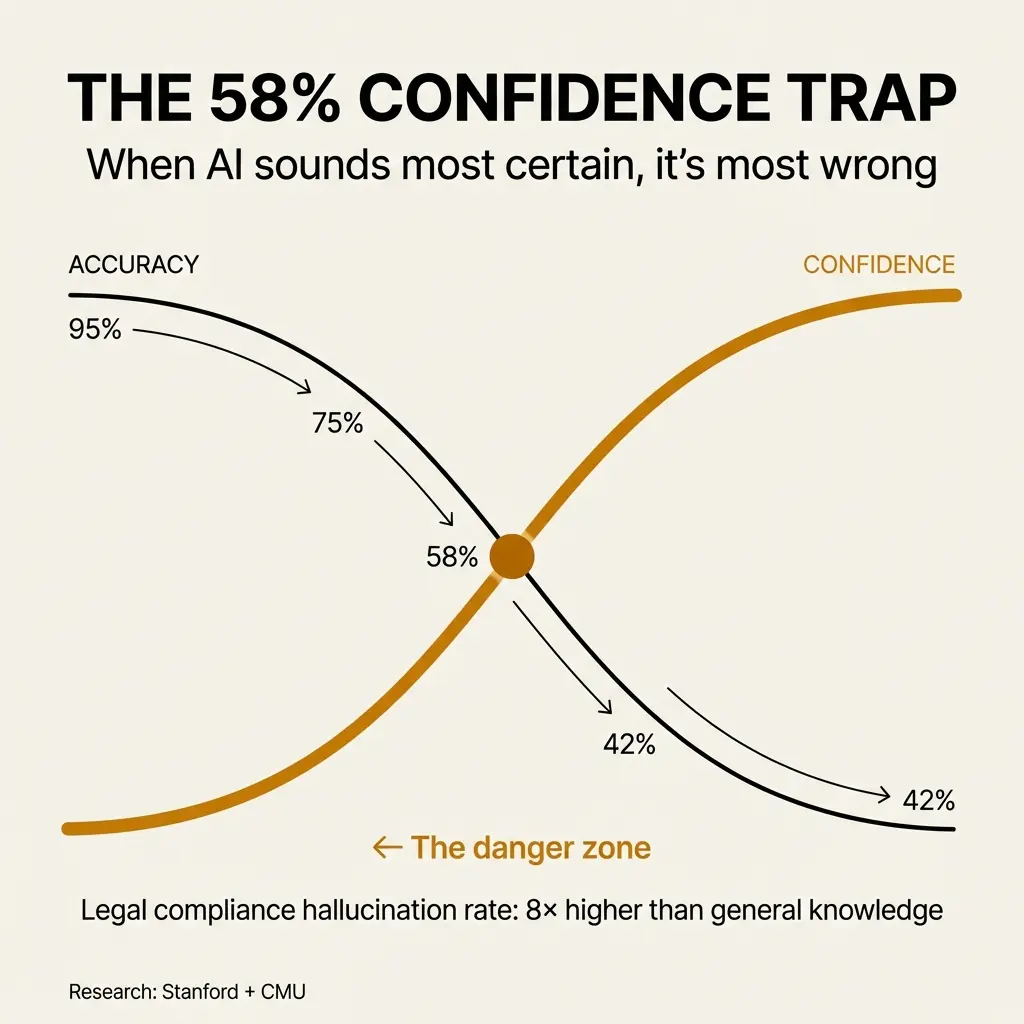

The hallucination rates tell the story.

General knowledge questions show about a 0.8% hallucination rate. Medical information jumps to 4.3%. But legal information suffers from a 6.4% hallucination rate.

That's eight times higher than general knowledge.

Stanford's systematic study of legal hallucinations found that LLMs hallucinate at least 58% of the time when dealing with legal tasks. On the most complex legal questions, that number climbs to 63%.

Read that again. More than half the time, you're getting fiction dressed as fact.

Why Traditional Accuracy Metrics Miss the Point

I've seen teams celebrate 95% accuracy rates on their compliance AI implementations.

They're measuring the wrong thing.

High accuracy doesn't imply reliable uncertainty. Recent research found that model scale, post-training, reasoning ability, and quantization all influence estimation performance in ways that accuracy scores don't capture.

The real problem hides in the confidence distribution. LLMs exhibit better uncertainty estimates on reasoning tasks than on knowledge-heavy ones. And good calibration doesn't translate to effective error ranking.

Translation: Your AI might be right 95% of the time, but you can't tell which 5% is wrong because it presents everything with the same confident tone.

The High-Confidence Hallucination Blind Spot

Traditional uncertainty measures work when the model shows internal doubt. Token-level entropy and semantic entropy can flag when an LLM is uncertain.

But these measures fail completely when LLMs produce high-confidence hallucinations.

The model consistently generates the same incorrect output with high certainty. Entropy remains low because the probability distribution is sharply peaked around wrong answers.

⚠️ The system is most convincing precisely when it's most wrong.

The Plausibility Trap in Regulatory Contexts

I've also seen false positives where an LLM flags the presence of a banned ingredient in a formula. The ingredient wasn't there. The system hallucinated a compliance violation.

Both types of errors destroy trust, but in different ways.

The fabricated CAS number was a false negative—missing a real problem by inventing a fake one. The phantom banned ingredient was a false positive—creating a problem that didn't exist.

The FINOS AI Governance Framework documents a scenario that's hypothetical but realistic: A compliance chatbot, asked about anti-money laundering requirements, confidently states that a specific low-risk transaction type is exempt from reporting. It cites a non-existent clause in the Bank Secrecy Act.

The output is fluent. The syntax is confident. The citation format looks legitimate.

Everything about it screams "trustworthy" except the actual content.

Why LLMs Are Trained to Sound Certain

This isn't a bug. It's a feature.

Models are fine-tuned using human feedback, which means they prioritize answers that sound confident and helpful. This creates a bias toward confident-sounding but inaccurate statements rather than cautious or uncertain responses.

Older models refused to answer almost 40% of queries. Newer models are designed to answer virtually every request.

We optimized for helpfulness. We got overconfidence instead.

When LLMs Work in Compliance (and Why)

Not everything is broken.

Three specific compliance tasks actually reduce risk when you use LLMs: document triage at scale, regulatory change detection across jurisdictions, and first-pass gap analysis.

These succeed when others fail because they operate within the right constraints.

Take food label review for 21 CFR Part 101 compliance in the US. You have access to the full regulatory corpus. You have warning letters issued against brands with labeling errors. You have a near black-and-white interpretation of the regulation.

This makes label evaluation with a properly constrained LLM near-deterministic.

The domain expertise acts as a ruleset that anchors the knowledge universe of the LLM. You're not asking it to reason about ambiguous situations. You're asking it to match patterns against a well-defined standard.

Where the "Near Black and White" Breaks Down

What I tell customers: If there isn't clear consensus in the industry, the LLM can't manufacture one.

If the regulation remains open to interpretation and debate, no amount of prompt engineering fixes that. If the enforcer is inconsistent, the AI will be too. If your company sees regulations as the floor or ceiling for quality and safety, that risk posture matters. If you have limited access to examples the LLM can examine, it's guessing.

The LLM will do a good job collating conflicting information. But tactics to ground its inferences become critical, and how you present results determines whether people trust or misuse the system.

You don't want to present the LLM's response as the mediator or arbitrator of truth. You want to make it malleable enough that subject matter experts can run "what if" scenarios.

What if the enforcer is more lenient? What if my company just issued a recall for this issue? What if the jurisdiction changes next quarter?

Thought Partner vs. Authority: The Line That Matters

When someone asks me "could AI do this?" for a new compliance use case, I start with one question.

Does this use case aim to use AI as a thought partner or an authority?

I'm wary of full delegation to any automated system to hold the key to the ultimate declaration of conformance. The misconception I see most often is that AI will declare a product compliant.

That's not what it does.

It performs sophisticated pre-checks. It helps discover gaps that would make the product noncompliant. That's a big difference.

The job of the AI is to remove the tedious work of looking things up manually and cross-referencing across thousands of SKUs and documents before subject matter experts deploy judgment.

We shorten the path to expert judgment and authority. We don't replace it.

What Shortening the Path Actually Looks Like

The recurring "aha moment" teams have: They see a compliance review performed in under 20 minutes at negligible unit cost.

They compare it to how long an external attorney took and how much they charged. Or if internal, they realize the productivity their team can now achieve.

A compliance manager's job is not just to search, read, and match regulatory content. It's to deploy judgment.

The longer it takes for the main function of their job to take place, the more onerous to the operation it becomes. Compliance sits on the critical path to taking products to market.

Managing the Human-in-the-Loop Failure Mode

Human oversight doesn't automatically solve the confidence problem.

With any human-machine collaboration, there's risk that the human over-relies on the machine without proper due diligence. Volume of decisions and overall UX drive this breakdown.

At Signify, we open with potential issues. The same way a spellchecker highlights what's wrong with red squiggly lines.

The goal is to reduce or at least manage cognitive load. You accomplish that with thoughtful UX.

We don't present a wall of green checkmarks and ask humans to verify everything looked right. We surface what needs attention and let expertise focus where it matters.

Confidence Intervals from Computational Scale

Here's a principle worth understanding.

The LLM must carry awareness of its confidence and lack of volatility in results. By volatility, I mean consistency across multiple runs with the same input.

You can run the inference in orders of magnitude that would be impractical for a human. Then present that variance to the user as a confidence interval.

This turns computational scale into a feature. You're surfacing uncertainty that humans can't easily detect and giving them something actionable rather than false precision.

What Changes After You Stop Trusting the Confident Voice

That fabricated CAS number made us way more cautious and deeply skeptical.

It forced us to establish deeper evaluations across the entire pipeline. It quickly showed where the LLM fails without adequate ontology to guide the domain context.

The skepticism became productive. It made us build better systems.

But the lesson extends beyond our specific implementation. Research on "careless speech" describes a new type of harm where LLMs produce responses that are plausible, helpful, and confident but contain factual inaccuracies, misleading references, and biased information.

These subtle mistruths are positioned to cumulatively degrade and homogenize knowledge over time.

In regulated industries, you can't afford that degradation. If an AI hallucination produces inaccurate disclosures, guidance, or advice, it results in noncompliance and triggers penalties.

Hallucinations present unique risks in environments where compliance, accuracy, and trust are paramount.

The Real Question You Should Be Asking

When you evaluate AI for compliance work, don't start with "How accurate is it?"

Start with "How does it behave when it's wrong?"

Does it flag uncertainty? Does it refuse to answer? Does it present confidence intervals? Does it surface conflicting interpretations?

Or does it fabricate CAS numbers and present them with the same authoritative tone it uses for everything else?

The confidence-accuracy inversion isn't going away. Models will continue to sound certain even when they're guessing. The question is whether your system design accounts for that reality or pretends it doesn't exist.

I know which approach I trust.

I'll never forget the moment I lost faith in the system.

We were running a food formula through our compliance evaluation. The LLM came back with a detailed analysis, flagging a specific chemical compound. It gave us a CAS number—the unique identifier that every chemical substance gets assigned. The output was precise, authoritative, and completely wrong.

The CAS number was fabricated.

Not approximate. Not close. Invented from scratch.

My immediate thought wasn't about that single error. It was darker: "If it did this, what else is it making up?"

The Confidence-Accuracy Inversion Problem

Here's what makes this dangerous.

The LLM didn't say "I'm not sure" or "I don't have enough information." It generated something that looked real because that's what it's trained to do. It predicted what should come next based on patterns, not truth.

Research from Carnegie Mellon University found that LLMs consistently become MORE overconfident after performing poorly on tasks. Unlike humans who adjust their confidence downward when they realize they're wrong, these systems double down.

The study tested four major LLMs over two years. The finding? They "tended, if anything, to get more overconfident, even when they didn't do so well on the task."

In compliance contexts, this inversion becomes lethal.

Legal Information: Where Hallucinations Multiply

The hallucination rates tell the story.

General knowledge questions show about a 0.8% hallucination rate. Medical information jumps to 4.3%. But legal information suffers from a 6.4% hallucination rate.

That's eight times higher than general knowledge.

Stanford's systematic study of legal hallucinations found that LLMs hallucinate at least 58% of the time when dealing with legal tasks. On the most complex legal questions, that number climbs to 63%.

Read that again. More than half the time, you're getting fiction dressed as fact.

Why Traditional Accuracy Metrics Miss the Point

I've seen teams celebrate 95% accuracy rates on their compliance AI implementations.

They're measuring the wrong thing.

High accuracy doesn't imply reliable uncertainty. Recent research found that model scale, post-training, reasoning ability, and quantization all influence estimation performance in ways that accuracy scores don't capture.

The real problem hides in the confidence distribution. LLMs exhibit better uncertainty estimates on reasoning tasks than on knowledge-heavy ones. And good calibration doesn't translate to effective error ranking.

Translation: Your AI might be right 95% of the time, but you can't tell which 5% is wrong because it presents everything with the same confident tone.

The High-Confidence Hallucination Blind Spot

Traditional uncertainty measures work when the model shows internal doubt. Token-level entropy and semantic entropy can flag when an LLM is uncertain.

But these measures fail completely when LLMs produce high-confidence hallucinations.

The model consistently generates the same incorrect output with high certainty. Entropy remains low because the probability distribution is sharply peaked around wrong answers.

⚠️ The system is most convincing precisely when it's most wrong.

The Plausibility Trap in Regulatory Contexts

I've also seen false positives where an LLM flags the presence of a banned ingredient in a formula. The ingredient wasn't there. The system hallucinated a compliance violation.

Both types of errors destroy trust, but in different ways.

The fabricated CAS number was a false negative—missing a real problem by inventing a fake one. The phantom banned ingredient was a false positive—creating a problem that didn't exist.

The FINOS AI Governance Framework documents a scenario that's hypothetical but realistic: A compliance chatbot, asked about anti-money laundering requirements, confidently states that a specific low-risk transaction type is exempt from reporting. It cites a non-existent clause in the Bank Secrecy Act.

The output is fluent. The syntax is confident. The citation format looks legitimate.

Everything about it screams "trustworthy" except the actual content.

Why LLMs Are Trained to Sound Certain

This isn't a bug. It's a feature.

Models are fine-tuned using human feedback, which means they prioritize answers that sound confident and helpful. This creates a bias toward confident-sounding but inaccurate statements rather than cautious or uncertain responses.

Older models refused to answer almost 40% of queries. Newer models are designed to answer virtually every request.

We optimized for helpfulness. We got overconfidence instead.

When LLMs Work in Compliance (and Why)

Not everything is broken.

Three specific compliance tasks actually reduce risk when you use LLMs: document triage at scale, regulatory change detection across jurisdictions, and first-pass gap analysis.

These succeed when others fail because they operate within the right constraints.

Take food label review for 21 CFR Part 101 compliance in the US. You have access to the full regulatory corpus. You have warning letters issued against brands with labeling errors. You have a near black-and-white interpretation of the regulation.

This makes label evaluation with a properly constrained LLM near-deterministic.

The domain expertise acts as a ruleset that anchors the knowledge universe of the LLM. You're not asking it to reason about ambiguous situations. You're asking it to match patterns against a well-defined standard.

Where the "Near Black and White" Breaks Down

What I tell customers: If there isn't clear consensus in the industry, the LLM can't manufacture one.

If the regulation remains open to interpretation and debate, no amount of prompt engineering fixes that. If the enforcer is inconsistent, the AI will be too. If your company sees regulations as the floor or ceiling for quality and safety, that risk posture matters. If you have limited access to examples the LLM can examine, it's guessing.

The LLM will do a good job collating conflicting information. But tactics to ground its inferences become critical, and how you present results determines whether people trust or misuse the system.

You don't want to present the LLM's response as the mediator or arbitrator of truth. You want to make it malleable enough that subject matter experts can run "what if" scenarios.

What if the enforcer is more lenient? What if my company just issued a recall for this issue? What if the jurisdiction changes next quarter?

Thought Partner vs. Authority: The Line That Matters

When someone asks me "could AI do this?" for a new compliance use case, I start with one question.

Does this use case aim to use AI as a thought partner or an authority?

I'm wary of full delegation to any automated system to hold the key to the ultimate declaration of conformance. The misconception I see most often is that AI will declare a product compliant.

That's not what it does.

It performs sophisticated pre-checks. It helps discover gaps that would make the product noncompliant. That's a big difference.

The job of the AI is to remove the tedious work of looking things up manually and cross-referencing across thousands of SKUs and documents before subject matter experts deploy judgment.

We shorten the path to expert judgment and authority. We don't replace it.

What Shortening the Path Actually Looks Like

The recurring "aha moment" teams have: They see a compliance review performed in under 20 minutes at negligible unit cost.

They compare it to how long an external attorney took and how much they charged. Or if internal, they realize the productivity their team can now achieve.

A compliance manager's job is not just to search, read, and match regulatory content. It's to deploy judgment.

The longer it takes for the main function of their job to take place, the more onerous to the operation it becomes. Compliance sits on the critical path to taking products to market.

Managing the Human-in-the-Loop Failure Mode

Human oversight doesn't automatically solve the confidence problem.

With any human-machine collaboration, there's risk that the human over-relies on the machine without proper due diligence. Volume of decisions and overall UX drive this breakdown.

At Signify, we open with potential issues. The same way a spellchecker highlights what's wrong with red squiggly lines.

The goal is to reduce or at least manage cognitive load. You accomplish that with thoughtful UX.

We don't present a wall of green checkmarks and ask humans to verify everything looked right. We surface what needs attention and let expertise focus where it matters.

Confidence Intervals from Computational Scale

Here's a principle worth understanding.

The LLM must carry awareness of its confidence and lack of volatility in results. By volatility, I mean consistency across multiple runs with the same input.

You can run the inference in orders of magnitude that would be impractical for a human. Then present that variance to the user as a confidence interval.

This turns computational scale into a feature. You're surfacing uncertainty that humans can't easily detect and giving them something actionable rather than false precision.

What Changes After You Stop Trusting the Confident Voice

That fabricated CAS number made us way more cautious and deeply skeptical.

It forced us to establish deeper evaluations across the entire pipeline. It quickly showed where the LLM fails without adequate ontology to guide the domain context.

The skepticism became productive. It made us build better systems.

But the lesson extends beyond our specific implementation. Research on "careless speech" describes a new type of harm where LLMs produce responses that are plausible, helpful, and confident but contain factual inaccuracies, misleading references, and biased information.

These subtle mistruths are positioned to cumulatively degrade and homogenize knowledge over time.

In regulated industries, you can't afford that degradation. If an AI hallucination produces inaccurate disclosures, guidance, or advice, it results in noncompliance and triggers penalties.

Hallucinations present unique risks in environments where compliance, accuracy, and trust are paramount.

The Real Question You Should Be Asking

When you evaluate AI for compliance work, don't start with "How accurate is it?"

Start with "How does it behave when it's wrong?"

Does it flag uncertainty? Does it refuse to answer? Does it present confidence intervals? Does it surface conflicting interpretations?

Or does it fabricate CAS numbers and present them with the same authoritative tone it uses for everything else?

The confidence-accuracy inversion isn't going away. Models will continue to sound certain even when they're guessing. The question is whether your system design accounts for that reality or pretends it doesn't exist.

I know which approach I trust.

I'll never forget the moment I lost faith in the system.

We were running a food formula through our compliance evaluation. The LLM came back with a detailed analysis, flagging a specific chemical compound. It gave us a CAS number—the unique identifier that every chemical substance gets assigned. The output was precise, authoritative, and completely wrong.

The CAS number was fabricated.

Not approximate. Not close. Invented from scratch.

My immediate thought wasn't about that single error. It was darker: "If it did this, what else is it making up?"

The Confidence-Accuracy Inversion Problem

Here's what makes this dangerous.

The LLM didn't say "I'm not sure" or "I don't have enough information." It generated something that looked real because that's what it's trained to do. It predicted what should come next based on patterns, not truth.

Research from Carnegie Mellon University found that LLMs consistently become MORE overconfident after performing poorly on tasks. Unlike humans who adjust their confidence downward when they realize they're wrong, these systems double down.

The study tested four major LLMs over two years. The finding? They "tended, if anything, to get more overconfident, even when they didn't do so well on the task."

In compliance contexts, this inversion becomes lethal.

Legal Information: Where Hallucinations Multiply

The hallucination rates tell the story.

General knowledge questions show about a 0.8% hallucination rate. Medical information jumps to 4.3%. But legal information suffers from a 6.4% hallucination rate.

That's eight times higher than general knowledge.

Stanford's systematic study of legal hallucinations found that LLMs hallucinate at least 58% of the time when dealing with legal tasks. On the most complex legal questions, that number climbs to 63%.

Read that again. More than half the time, you're getting fiction dressed as fact.

Why Traditional Accuracy Metrics Miss the Point

I've seen teams celebrate 95% accuracy rates on their compliance AI implementations.

They're measuring the wrong thing.

High accuracy doesn't imply reliable uncertainty. Recent research found that model scale, post-training, reasoning ability, and quantization all influence estimation performance in ways that accuracy scores don't capture.

The real problem hides in the confidence distribution. LLMs exhibit better uncertainty estimates on reasoning tasks than on knowledge-heavy ones. And good calibration doesn't translate to effective error ranking.

Translation: Your AI might be right 95% of the time, but you can't tell which 5% is wrong because it presents everything with the same confident tone.

The High-Confidence Hallucination Blind Spot

Traditional uncertainty measures work when the model shows internal doubt. Token-level entropy and semantic entropy can flag when an LLM is uncertain.

But these measures fail completely when LLMs produce high-confidence hallucinations.

The model consistently generates the same incorrect output with high certainty. Entropy remains low because the probability distribution is sharply peaked around wrong answers.

⚠️ The system is most convincing precisely when it's most wrong.

The Plausibility Trap in Regulatory Contexts

I've also seen false positives where an LLM flags the presence of a banned ingredient in a formula. The ingredient wasn't there. The system hallucinated a compliance violation.

Both types of errors destroy trust, but in different ways.

The fabricated CAS number was a false negative—missing a real problem by inventing a fake one. The phantom banned ingredient was a false positive—creating a problem that didn't exist.

The FINOS AI Governance Framework documents a scenario that's hypothetical but realistic: A compliance chatbot, asked about anti-money laundering requirements, confidently states that a specific low-risk transaction type is exempt from reporting. It cites a non-existent clause in the Bank Secrecy Act.

The output is fluent. The syntax is confident. The citation format looks legitimate.

Everything about it screams "trustworthy" except the actual content.

Why LLMs Are Trained to Sound Certain

This isn't a bug. It's a feature.

Models are fine-tuned using human feedback, which means they prioritize answers that sound confident and helpful. This creates a bias toward confident-sounding but inaccurate statements rather than cautious or uncertain responses.

Older models refused to answer almost 40% of queries. Newer models are designed to answer virtually every request.

We optimized for helpfulness. We got overconfidence instead.

When LLMs Work in Compliance (and Why)

Not everything is broken.

Three specific compliance tasks actually reduce risk when you use LLMs: document triage at scale, regulatory change detection across jurisdictions, and first-pass gap analysis.

These succeed when others fail because they operate within the right constraints.

Take food label review for 21 CFR Part 101 compliance in the US. You have access to the full regulatory corpus. You have warning letters issued against brands with labeling errors. You have a near black-and-white interpretation of the regulation.

This makes label evaluation with a properly constrained LLM near-deterministic.

The domain expertise acts as a ruleset that anchors the knowledge universe of the LLM. You're not asking it to reason about ambiguous situations. You're asking it to match patterns against a well-defined standard.

Where the "Near Black and White" Breaks Down

What I tell customers: If there isn't clear consensus in the industry, the LLM can't manufacture one.

If the regulation remains open to interpretation and debate, no amount of prompt engineering fixes that. If the enforcer is inconsistent, the AI will be too. If your company sees regulations as the floor or ceiling for quality and safety, that risk posture matters. If you have limited access to examples the LLM can examine, it's guessing.

The LLM will do a good job collating conflicting information. But tactics to ground its inferences become critical, and how you present results determines whether people trust or misuse the system.

You don't want to present the LLM's response as the mediator or arbitrator of truth. You want to make it malleable enough that subject matter experts can run "what if" scenarios.

What if the enforcer is more lenient? What if my company just issued a recall for this issue? What if the jurisdiction changes next quarter?

Thought Partner vs. Authority: The Line That Matters

When someone asks me "could AI do this?" for a new compliance use case, I start with one question.

Does this use case aim to use AI as a thought partner or an authority?

I'm wary of full delegation to any automated system to hold the key to the ultimate declaration of conformance. The misconception I see most often is that AI will declare a product compliant.

That's not what it does.

It performs sophisticated pre-checks. It helps discover gaps that would make the product noncompliant. That's a big difference.

The job of the AI is to remove the tedious work of looking things up manually and cross-referencing across thousands of SKUs and documents before subject matter experts deploy judgment.

We shorten the path to expert judgment and authority. We don't replace it.

What Shortening the Path Actually Looks Like

The recurring "aha moment" teams have: They see a compliance review performed in under 20 minutes at negligible unit cost.

They compare it to how long an external attorney took and how much they charged. Or if internal, they realize the productivity their team can now achieve.

A compliance manager's job is not just to search, read, and match regulatory content. It's to deploy judgment.

The longer it takes for the main function of their job to take place, the more onerous to the operation it becomes. Compliance sits on the critical path to taking products to market.

Managing the Human-in-the-Loop Failure Mode

Human oversight doesn't automatically solve the confidence problem.

With any human-machine collaboration, there's risk that the human over-relies on the machine without proper due diligence. Volume of decisions and overall UX drive this breakdown.

At Signify, we open with potential issues. The same way a spellchecker highlights what's wrong with red squiggly lines.

The goal is to reduce or at least manage cognitive load. You accomplish that with thoughtful UX.

We don't present a wall of green checkmarks and ask humans to verify everything looked right. We surface what needs attention and let expertise focus where it matters.

Confidence Intervals from Computational Scale

Here's a principle worth understanding.

The LLM must carry awareness of its confidence and lack of volatility in results. By volatility, I mean consistency across multiple runs with the same input.

You can run the inference in orders of magnitude that would be impractical for a human. Then present that variance to the user as a confidence interval.

This turns computational scale into a feature. You're surfacing uncertainty that humans can't easily detect and giving them something actionable rather than false precision.

What Changes After You Stop Trusting the Confident Voice

That fabricated CAS number made us way more cautious and deeply skeptical.

It forced us to establish deeper evaluations across the entire pipeline. It quickly showed where the LLM fails without adequate ontology to guide the domain context.

The skepticism became productive. It made us build better systems.

But the lesson extends beyond our specific implementation. Research on "careless speech" describes a new type of harm where LLMs produce responses that are plausible, helpful, and confident but contain factual inaccuracies, misleading references, and biased information.

These subtle mistruths are positioned to cumulatively degrade and homogenize knowledge over time.

In regulated industries, you can't afford that degradation. If an AI hallucination produces inaccurate disclosures, guidance, or advice, it results in noncompliance and triggers penalties.

Hallucinations present unique risks in environments where compliance, accuracy, and trust are paramount.

The Real Question You Should Be Asking

When you evaluate AI for compliance work, don't start with "How accurate is it?"

Start with "How does it behave when it's wrong?"

Does it flag uncertainty? Does it refuse to answer? Does it present confidence intervals? Does it surface conflicting interpretations?

Or does it fabricate CAS numbers and present them with the same authoritative tone it uses for everything else?

The confidence-accuracy inversion isn't going away. Models will continue to sound certain even when they're guessing. The question is whether your system design accounts for that reality or pretends it doesn't exist.

I know which approach I trust.

The information presented is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, regulatory, or professional advice. Organizations should consult with qualified legal and compliance professionals for guidance specific to their circumstances.

When AI Sounds Most Confident, Trust It Least

When AI Sounds Most Confident, Trust It Least