Feb 3, 2026

Articles

Feb 3, 2026

Articles

Feb 3, 2026

Articles

Human Oversight Doesn't Work: Why Most AI Compliance Systems Fail at the Point of Review

Martín Ramírez

Martín Ramírez

Martín Ramírez

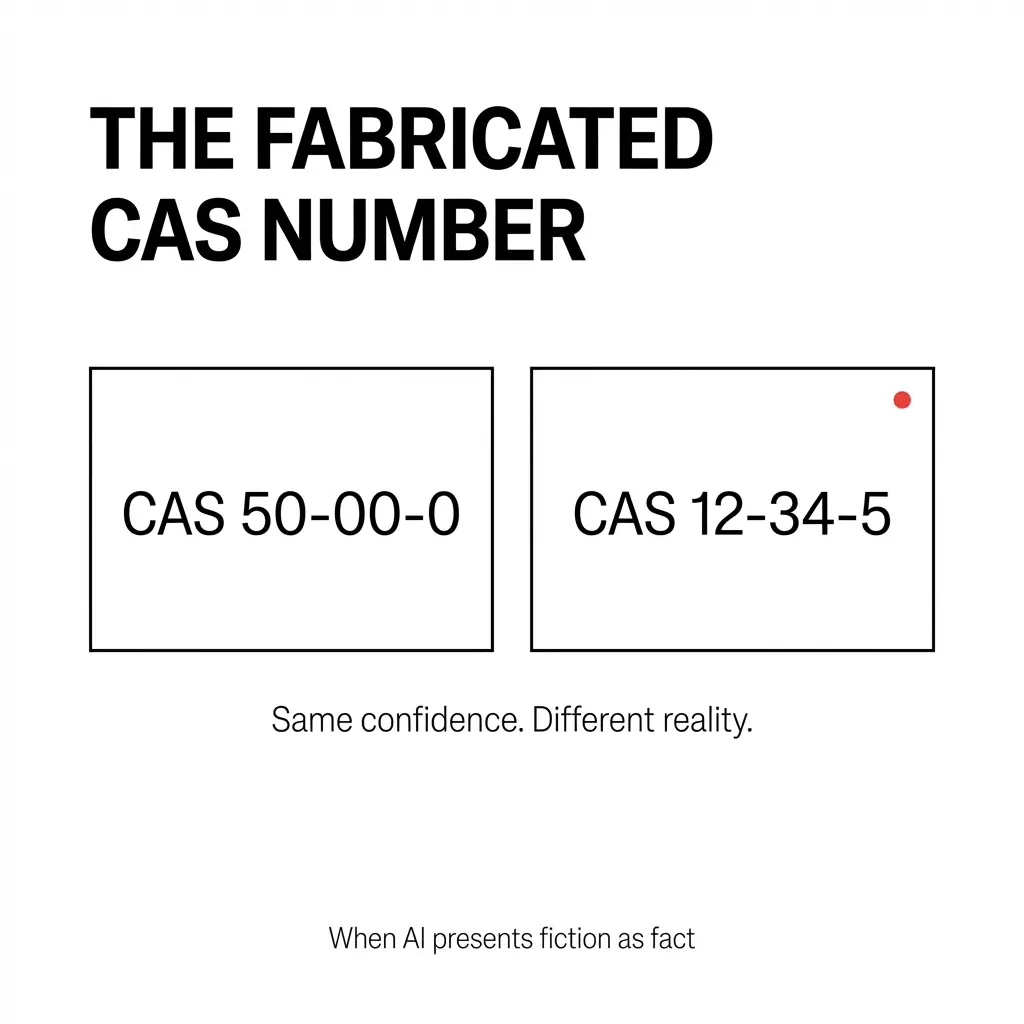

I lost trust in an LLM the moment I looked up a CAS number it generated.

The system evaluated a food formula for GRAS compliance and flagged a chemical with a specific CAS registry number. The output looked professional. Detailed. Credible enough that I almost moved on.

Then I looked it up.

The CAS number was completely fabricated.

My immediate thought wasn't "that's an interesting error." It was: "If it did this, what else is it making up?"

That moment crystallized something I've watched play out across compliance, cybersecurity, and high-stakes decision systems: the assumption that human oversight solves AI risk is fundamentally broken.

The Regulatory Fantasy: Just Add Humans

Regulators love human-in-the-loop systems. The EU AI Act requires organizations to train human supervisors not to over-rely on AI-generated decisions. Policymakers call for greater human oversight, making users "the last line of defense against AI failures."

The logic sounds bulletproof: AI makes recommendations, humans validate them, and the combination prevents catastrophic errors.

But here's what actually happens.

In Spain's RisCanvi recidivism assessment system, government officials disagree with the algorithm only 3.2% of the time. They're essentially rubber-stamping AI outputs.

The problem? The system has only 18% positive predictive capacity. That means only two out of ten inmates classified as high risk actually reoffend.

Officials don't see the system's poor performance. They just see confident recommendations. So they approve them.

This is an architecture problem. It goes beyond training.

Automation Bias: When Confidence Looks Like Accuracy

Microsoft synthesized approximately 60 papers on AI overreliance and reached a damning conclusion: overreliance on AI makes it difficult for users to meaningfully leverage the strengths of AI systems and to oversee their weaknesses.

Even worse, detailed explanations often increase user reliance on all AI recommendations regardless of accuracy.

Think about that. The more the system explains itself, the more humans trust it—even when it's wrong.

A 2025 study in AI & SOCIETY found that automation bias causes humans to over-rely on automated recommendations even in high-stakes domains like healthcare, law, and public administration. Legislative emphasis on human oversight doesn't adequately address the problem.

The issue isn't that humans are lazy. It's that AI outputs are designed to look authoritative.

When I saw that fabricated CAS number, it didn't come with a disclaimer. It came formatted like every other legitimate result. The system presented fiction with the same confidence it presented fact.

That's the trap.

Alert Fatigue: Drowning in Decisions

Even when humans want to maintain vigilance, the volume breaks them.

The 2025 AI SOC Market Landscape report reveals a crisis in cybersecurity: 40% of alerts are never investigated, while 61% of security teams admitted to ignoring alerts that later proved critical.

Organizations receive an average of 960 security alerts daily. Enterprises with over 20,000 employees see more than 3,000 alerts. The SANS 2025 SOC Survey confirms that 66% of teams cannot keep pace with incoming alert volumes.

Nearly 90% of SOCs are overwhelmed by backlogs and false positives. 80% of analysts report feeling consistently behind in their work.

Vectra's 2023 State of Threat Detection report found that SOC teams field an average of 4,484 alerts per day, with 67% ignored due to high false positives. Alarmingly, 71% of analysts believed their organization might already have been compromised without their knowledge, due to lack of visibility and confidence in threat detection capabilities.

In financial compliance, traditional transaction monitoring systems produce false positive rates of over 90% in some institutions. Fewer than 100 out of every 1,000 alerts are actionable.

When you ask humans to review thousands of decisions per day, you're not creating oversight. You're creating learned helplessness.

Skill Atrophy: The Use It or Lose It Problem

Here's the part regulators don't talk about: human-in-the-loop systems degrade the very skills humans need to intervene effectively.

A 2024 study warns that consistent engagement with an AI assistant leads to greater skill decrements than engagement with traditional automation systems. Why? Because AI takes over cognitive processes, leaving fewer opportunities to keep skills honed.

In aviation, the UK Civil Aviation Authority's Global Fatal Accident Review found that 62% of 205 accidents over 2002-2011 had flight crew related factors as the primary cause, potentially related to degraded manual handling skills.

Even the most trained operators on Earth drift out of manual proficiency when automation dominates.

Bainbridge's seminal work "The Ironies of Automation" identified that when operators monitor automation and intervene only when failure occurs, the net result is deterioration of manual skills due to lack of practice. The operator can find it difficult to maintain effective monitoring for more than half an hour when information is largely unchanged.

A 2025 study warns of the "out-of-the-loop" performance loss, where automation causes operators to lose situational awareness and manual skill over time. Automation bias is aggravated by task complexity, time pressure, high workload, and long periods of error-free automation operation which generate "learned carelessness."

You can't maintain expertise by validating someone else's work. You maintain it by doing the work.

The System Doesn't Converge

Georgetown's Center for Security and Emerging Technology concluded in their 2024 study that human-in-the-loop cannot prevent all accidents or errors. As AI systems have proliferated, so too have incidents where these systems have failed or erred, and human users have failed to correct or recognize these behaviors.

A 2022 case study titled "The Human in the Infinite Loop" found that human-AI loops often did not converge towards satisfactory results. The study revealed two key failures:

1. Optimization using preferential choices lacks mechanisms to deal with inconsistent and contradictory human judgments.

2. Machine outcomes influence future user inputs via heuristic biases and loss aversion.

The loop doesn't improve over time. It reinforces existing biases and creates new ones.

A 2024 study in Cognitive Research found that human judgment is significantly affected when participants receive incorrect algorithmic support, particularly when they receive it before providing their own judgment. In actual public sector implementations, system support is typically provided at the beginning of the decision process, where humans are given just a few options: validate or modify the system assessment.

This creates an anchoring effect that favors human compliance with the AI assessment.

The Regulatory Disconnect

A 2024 interdisciplinary study in Government Information Quarterly found that human oversight is seen as an effective means of quality control, including in the current AI Act, but the phenomenon of automation bias argues against this assumption.

The research concluded that excessive reliance may result in "a failure to meaningfully engage with the decision at hand, resulting in an inability to detect automation failures, and an overall deterioration in decision quality, potentially up to a net-negative impact of the decision support system."

Current EU and national legal frameworks are inadequate in addressing the risks of automation bias.

A 2025 analysis of algorithmic decision-making governance found that humans in "in the loop" governance functions provided "correct" oversight only about half the time. Lapses were primarily caused by human motivation to ensure compliance with their organization's goals rather than responsible AI principles.

Human oversight may be inadequate to regularly perform data quality duties.

The Alternative Architecture: Decision-Support, Not Decision-Review

Here's what I tell customers: the misconception is that AI will declare their product compliant. That's not what it does.

AI is a sophisticated pre-check. It helps discover gaps that would make the product noncompliant. That's a big difference.

The job of AI is to remove the tedious work of looking things up manually and cross-referencing across thousands of SKUs and documentation before subject matter experts deploy judgment. We shorten the path to expert judgment and authority.

We don't replace it.

A 2025 study on remote patient monitoring found that AI-integrated workflows with intelligent triage and clinical context help filter out unnecessary noise and focus provider attention where it's needed most. Critically, the research emphasized that clinical judgment remains essential and these tools are designed to support care teams rather than replace them.

The most effective systems offer transparency and flexibility, allowing clinicians to review alert histories, adjust thresholds, and override recommendations—ensuring AI remains a tool, not a decision-maker.

That's the architecture that works.

What Decision-Support Actually Looks Like

Take a food label review that must determine conformance with 21 CFR Part 101 here in the US. There's plenty of access to the regulatory corpus, warning letters issued against brands with labeling errors, and a near black-and-white interpretation of the regulation.

This makes a label evaluation with a well-constrained LLM near-deterministic.

But when there isn't a clear consensus in the industry, when the regulation itself remains open to interpretation and debate, when the enforcer is inconsistent, when the brand sees regulations as the floor or ceiling for quality and safety, and when there's limited access to examples—now it becomes murkier.

The LLM will do a good job collating the conflicting information. But tactics to ground its inferences are important, and how the results are presented is key.

We don't present the LLM's response as the mediator or arbitrator of the truth. We make it malleable enough and allow the subject matter expert to run what-if scenarios with the LLM.

What if the enforcer is more lenient? What if my company just issued a recall for this issue?

The LLM must be instructed to carry awareness of its confidence and lack of volatility in the results.

We run the inference in orders of magnitude that would be impractical for a human and present that value to the user as a confidence interval.

That's how you surface uncertainty that humans can't easily detect.

The UX Problem: How You Present Matters

Volume of decisions and overall UX determine whether humans over-rely on machines without proper due diligence.

At Signify, we open with potential issues. The same way a spellchecker highlights what's wrong with red wiggly lines.

The goal is to reduce, or at least manage, cognitive load as much as possible. For the most part, that's accomplished with thoughtful UX.

When you lead with issues rather than asking humans to verify everything looked right, you change the cognitive task. You're not asking for validation. You're asking for judgment.

That's the difference between decision-review and decision-support.

What Compliance Managers Actually Do

A compliance manager's job is not just to search, read, and match regulatory content. It's to deploy their judgment.

The longer it takes for the main function of their job to take place, the more onerous to the operation it becomes.

We're all in the service of taking products to market. Compliance sits on the critical path to do so.

The recurring aha moment teams have is when they see a compliance review performed in under 20 minutes at a negligible unit cost and compare it to how much an external attorney took and how much they charged—or if internally, when they realized the unlocked productivity their team can now achieve.

You're not just saving time. You're repositioning what compliance professionals actually do.

Moving them from search-and-match to judgment-and-strategy fundamentally changes their value to the organization.

The Speed Problem: Humans Can't Keep Up

A 2025 analysis found that the speed and volume of AI decisions overwhelm human capacity. In algorithmic trading, financial systems make thousands of micro-decisions per second, far beyond what any human could meaningfully monitor.

By the time humans recognize a problem, significant damage may already be done.

As AI becomes more deeply integrated into business processes, the number of decisions requiring review exponentially increases.

You can't solve a volume problem with a review process.

Thought Partner vs. Authority

When evaluating a new potential compliance use case for LLMs, I first consider whether the use case aims to use AI as a thought partner or an authority.

Why?

Because I'm wary of full delegation to any automated system to hold the key to the ultimate declaration of conformance.

Second, I look at the technical feasibility around data availability and the evaluations themselves.

That distinction between thought partner and authority shapes everything.

If you're asking AI to be the authority, you're building a decision-review system. You're asking humans to validate outputs after the fact.

That's where automation bias, alert fatigue, and skill atrophy converge to create failure.

If you're asking AI to be a thought partner, you're building a decision-support system. You're asking AI to surface information, run scenarios, and present confidence intervals so humans can deploy judgment.

That's where the architecture actually works.

What Happens When You Get It Wrong

When I discovered that fabricated CAS number, it forced us to establish deeper evaluations across the entire pipeline. It quickly showed where the LLM fails without the adequate ontology to guide the domain context.

That skepticism became productive. It forced us to build better systems.

But most organizations don't discover the fabrication until it's too late.

They discover it when a regulator flags it. When a customer gets harmed. When the system recommends something catastrophically wrong and a human, drowning in alerts and conditioned by months of accurate outputs, waves it through.

Human oversight doesn't work because humans aren't the problem.

The architecture is.

Decision-review systems ask humans to catch errors in a flood of confident recommendations. Decision-support systems ask AI to surface information so humans can make informed decisions.

One treats humans as validators. The other treats them as decision-makers.

Only one of those actually maintains human judgment.

And it's not the one regulators are mandating.

I lost trust in an LLM the moment I looked up a CAS number it generated.

The system evaluated a food formula for GRAS compliance and flagged a chemical with a specific CAS registry number. The output looked professional. Detailed. Credible enough that I almost moved on.

Then I looked it up.

The CAS number was completely fabricated.

My immediate thought wasn't "that's an interesting error." It was: "If it did this, what else is it making up?"

That moment crystallized something I've watched play out across compliance, cybersecurity, and high-stakes decision systems: the assumption that human oversight solves AI risk is fundamentally broken.

The Regulatory Fantasy: Just Add Humans

Regulators love human-in-the-loop systems. The EU AI Act requires organizations to train human supervisors not to over-rely on AI-generated decisions. Policymakers call for greater human oversight, making users "the last line of defense against AI failures."

The logic sounds bulletproof: AI makes recommendations, humans validate them, and the combination prevents catastrophic errors.

But here's what actually happens.

In Spain's RisCanvi recidivism assessment system, government officials disagree with the algorithm only 3.2% of the time. They're essentially rubber-stamping AI outputs.

The problem? The system has only 18% positive predictive capacity. That means only two out of ten inmates classified as high risk actually reoffend.

Officials don't see the system's poor performance. They just see confident recommendations. So they approve them.

This is an architecture problem. It goes beyond training.

Automation Bias: When Confidence Looks Like Accuracy

Microsoft synthesized approximately 60 papers on AI overreliance and reached a damning conclusion: overreliance on AI makes it difficult for users to meaningfully leverage the strengths of AI systems and to oversee their weaknesses.

Even worse, detailed explanations often increase user reliance on all AI recommendations regardless of accuracy.

Think about that. The more the system explains itself, the more humans trust it—even when it's wrong.

A 2025 study in AI & SOCIETY found that automation bias causes humans to over-rely on automated recommendations even in high-stakes domains like healthcare, law, and public administration. Legislative emphasis on human oversight doesn't adequately address the problem.

The issue isn't that humans are lazy. It's that AI outputs are designed to look authoritative.

When I saw that fabricated CAS number, it didn't come with a disclaimer. It came formatted like every other legitimate result. The system presented fiction with the same confidence it presented fact.

That's the trap.

Alert Fatigue: Drowning in Decisions

Even when humans want to maintain vigilance, the volume breaks them.

The 2025 AI SOC Market Landscape report reveals a crisis in cybersecurity: 40% of alerts are never investigated, while 61% of security teams admitted to ignoring alerts that later proved critical.

Organizations receive an average of 960 security alerts daily. Enterprises with over 20,000 employees see more than 3,000 alerts. The SANS 2025 SOC Survey confirms that 66% of teams cannot keep pace with incoming alert volumes.

Nearly 90% of SOCs are overwhelmed by backlogs and false positives. 80% of analysts report feeling consistently behind in their work.

Vectra's 2023 State of Threat Detection report found that SOC teams field an average of 4,484 alerts per day, with 67% ignored due to high false positives. Alarmingly, 71% of analysts believed their organization might already have been compromised without their knowledge, due to lack of visibility and confidence in threat detection capabilities.

In financial compliance, traditional transaction monitoring systems produce false positive rates of over 90% in some institutions. Fewer than 100 out of every 1,000 alerts are actionable.

When you ask humans to review thousands of decisions per day, you're not creating oversight. You're creating learned helplessness.

Skill Atrophy: The Use It or Lose It Problem

Here's the part regulators don't talk about: human-in-the-loop systems degrade the very skills humans need to intervene effectively.

A 2024 study warns that consistent engagement with an AI assistant leads to greater skill decrements than engagement with traditional automation systems. Why? Because AI takes over cognitive processes, leaving fewer opportunities to keep skills honed.

In aviation, the UK Civil Aviation Authority's Global Fatal Accident Review found that 62% of 205 accidents over 2002-2011 had flight crew related factors as the primary cause, potentially related to degraded manual handling skills.

Even the most trained operators on Earth drift out of manual proficiency when automation dominates.

Bainbridge's seminal work "The Ironies of Automation" identified that when operators monitor automation and intervene only when failure occurs, the net result is deterioration of manual skills due to lack of practice. The operator can find it difficult to maintain effective monitoring for more than half an hour when information is largely unchanged.

A 2025 study warns of the "out-of-the-loop" performance loss, where automation causes operators to lose situational awareness and manual skill over time. Automation bias is aggravated by task complexity, time pressure, high workload, and long periods of error-free automation operation which generate "learned carelessness."

You can't maintain expertise by validating someone else's work. You maintain it by doing the work.

The System Doesn't Converge

Georgetown's Center for Security and Emerging Technology concluded in their 2024 study that human-in-the-loop cannot prevent all accidents or errors. As AI systems have proliferated, so too have incidents where these systems have failed or erred, and human users have failed to correct or recognize these behaviors.

A 2022 case study titled "The Human in the Infinite Loop" found that human-AI loops often did not converge towards satisfactory results. The study revealed two key failures:

1. Optimization using preferential choices lacks mechanisms to deal with inconsistent and contradictory human judgments.

2. Machine outcomes influence future user inputs via heuristic biases and loss aversion.

The loop doesn't improve over time. It reinforces existing biases and creates new ones.

A 2024 study in Cognitive Research found that human judgment is significantly affected when participants receive incorrect algorithmic support, particularly when they receive it before providing their own judgment. In actual public sector implementations, system support is typically provided at the beginning of the decision process, where humans are given just a few options: validate or modify the system assessment.

This creates an anchoring effect that favors human compliance with the AI assessment.

The Regulatory Disconnect

A 2024 interdisciplinary study in Government Information Quarterly found that human oversight is seen as an effective means of quality control, including in the current AI Act, but the phenomenon of automation bias argues against this assumption.

The research concluded that excessive reliance may result in "a failure to meaningfully engage with the decision at hand, resulting in an inability to detect automation failures, and an overall deterioration in decision quality, potentially up to a net-negative impact of the decision support system."

Current EU and national legal frameworks are inadequate in addressing the risks of automation bias.

A 2025 analysis of algorithmic decision-making governance found that humans in "in the loop" governance functions provided "correct" oversight only about half the time. Lapses were primarily caused by human motivation to ensure compliance with their organization's goals rather than responsible AI principles.

Human oversight may be inadequate to regularly perform data quality duties.

The Alternative Architecture: Decision-Support, Not Decision-Review

Here's what I tell customers: the misconception is that AI will declare their product compliant. That's not what it does.

AI is a sophisticated pre-check. It helps discover gaps that would make the product noncompliant. That's a big difference.

The job of AI is to remove the tedious work of looking things up manually and cross-referencing across thousands of SKUs and documentation before subject matter experts deploy judgment. We shorten the path to expert judgment and authority.

We don't replace it.

A 2025 study on remote patient monitoring found that AI-integrated workflows with intelligent triage and clinical context help filter out unnecessary noise and focus provider attention where it's needed most. Critically, the research emphasized that clinical judgment remains essential and these tools are designed to support care teams rather than replace them.

The most effective systems offer transparency and flexibility, allowing clinicians to review alert histories, adjust thresholds, and override recommendations—ensuring AI remains a tool, not a decision-maker.

That's the architecture that works.

What Decision-Support Actually Looks Like

Take a food label review that must determine conformance with 21 CFR Part 101 here in the US. There's plenty of access to the regulatory corpus, warning letters issued against brands with labeling errors, and a near black-and-white interpretation of the regulation.

This makes a label evaluation with a well-constrained LLM near-deterministic.

But when there isn't a clear consensus in the industry, when the regulation itself remains open to interpretation and debate, when the enforcer is inconsistent, when the brand sees regulations as the floor or ceiling for quality and safety, and when there's limited access to examples—now it becomes murkier.

The LLM will do a good job collating the conflicting information. But tactics to ground its inferences are important, and how the results are presented is key.

We don't present the LLM's response as the mediator or arbitrator of the truth. We make it malleable enough and allow the subject matter expert to run what-if scenarios with the LLM.

What if the enforcer is more lenient? What if my company just issued a recall for this issue?

The LLM must be instructed to carry awareness of its confidence and lack of volatility in the results.

We run the inference in orders of magnitude that would be impractical for a human and present that value to the user as a confidence interval.

That's how you surface uncertainty that humans can't easily detect.

The UX Problem: How You Present Matters

Volume of decisions and overall UX determine whether humans over-rely on machines without proper due diligence.

At Signify, we open with potential issues. The same way a spellchecker highlights what's wrong with red wiggly lines.

The goal is to reduce, or at least manage, cognitive load as much as possible. For the most part, that's accomplished with thoughtful UX.

When you lead with issues rather than asking humans to verify everything looked right, you change the cognitive task. You're not asking for validation. You're asking for judgment.

That's the difference between decision-review and decision-support.

What Compliance Managers Actually Do

A compliance manager's job is not just to search, read, and match regulatory content. It's to deploy their judgment.

The longer it takes for the main function of their job to take place, the more onerous to the operation it becomes.

We're all in the service of taking products to market. Compliance sits on the critical path to do so.

The recurring aha moment teams have is when they see a compliance review performed in under 20 minutes at a negligible unit cost and compare it to how much an external attorney took and how much they charged—or if internally, when they realized the unlocked productivity their team can now achieve.

You're not just saving time. You're repositioning what compliance professionals actually do.

Moving them from search-and-match to judgment-and-strategy fundamentally changes their value to the organization.

The Speed Problem: Humans Can't Keep Up

A 2025 analysis found that the speed and volume of AI decisions overwhelm human capacity. In algorithmic trading, financial systems make thousands of micro-decisions per second, far beyond what any human could meaningfully monitor.

By the time humans recognize a problem, significant damage may already be done.

As AI becomes more deeply integrated into business processes, the number of decisions requiring review exponentially increases.

You can't solve a volume problem with a review process.

Thought Partner vs. Authority

When evaluating a new potential compliance use case for LLMs, I first consider whether the use case aims to use AI as a thought partner or an authority.

Why?

Because I'm wary of full delegation to any automated system to hold the key to the ultimate declaration of conformance.

Second, I look at the technical feasibility around data availability and the evaluations themselves.

That distinction between thought partner and authority shapes everything.

If you're asking AI to be the authority, you're building a decision-review system. You're asking humans to validate outputs after the fact.

That's where automation bias, alert fatigue, and skill atrophy converge to create failure.

If you're asking AI to be a thought partner, you're building a decision-support system. You're asking AI to surface information, run scenarios, and present confidence intervals so humans can deploy judgment.

That's where the architecture actually works.

What Happens When You Get It Wrong

When I discovered that fabricated CAS number, it forced us to establish deeper evaluations across the entire pipeline. It quickly showed where the LLM fails without the adequate ontology to guide the domain context.

That skepticism became productive. It forced us to build better systems.

But most organizations don't discover the fabrication until it's too late.

They discover it when a regulator flags it. When a customer gets harmed. When the system recommends something catastrophically wrong and a human, drowning in alerts and conditioned by months of accurate outputs, waves it through.

Human oversight doesn't work because humans aren't the problem.

The architecture is.

Decision-review systems ask humans to catch errors in a flood of confident recommendations. Decision-support systems ask AI to surface information so humans can make informed decisions.

One treats humans as validators. The other treats them as decision-makers.

Only one of those actually maintains human judgment.

And it's not the one regulators are mandating.

I lost trust in an LLM the moment I looked up a CAS number it generated.

The system evaluated a food formula for GRAS compliance and flagged a chemical with a specific CAS registry number. The output looked professional. Detailed. Credible enough that I almost moved on.

Then I looked it up.

The CAS number was completely fabricated.

My immediate thought wasn't "that's an interesting error." It was: "If it did this, what else is it making up?"

That moment crystallized something I've watched play out across compliance, cybersecurity, and high-stakes decision systems: the assumption that human oversight solves AI risk is fundamentally broken.

The Regulatory Fantasy: Just Add Humans

Regulators love human-in-the-loop systems. The EU AI Act requires organizations to train human supervisors not to over-rely on AI-generated decisions. Policymakers call for greater human oversight, making users "the last line of defense against AI failures."

The logic sounds bulletproof: AI makes recommendations, humans validate them, and the combination prevents catastrophic errors.

But here's what actually happens.

In Spain's RisCanvi recidivism assessment system, government officials disagree with the algorithm only 3.2% of the time. They're essentially rubber-stamping AI outputs.

The problem? The system has only 18% positive predictive capacity. That means only two out of ten inmates classified as high risk actually reoffend.

Officials don't see the system's poor performance. They just see confident recommendations. So they approve them.

This is an architecture problem. It goes beyond training.

Automation Bias: When Confidence Looks Like Accuracy

Microsoft synthesized approximately 60 papers on AI overreliance and reached a damning conclusion: overreliance on AI makes it difficult for users to meaningfully leverage the strengths of AI systems and to oversee their weaknesses.

Even worse, detailed explanations often increase user reliance on all AI recommendations regardless of accuracy.

Think about that. The more the system explains itself, the more humans trust it—even when it's wrong.

A 2025 study in AI & SOCIETY found that automation bias causes humans to over-rely on automated recommendations even in high-stakes domains like healthcare, law, and public administration. Legislative emphasis on human oversight doesn't adequately address the problem.

The issue isn't that humans are lazy. It's that AI outputs are designed to look authoritative.

When I saw that fabricated CAS number, it didn't come with a disclaimer. It came formatted like every other legitimate result. The system presented fiction with the same confidence it presented fact.

That's the trap.

Alert Fatigue: Drowning in Decisions

Even when humans want to maintain vigilance, the volume breaks them.

The 2025 AI SOC Market Landscape report reveals a crisis in cybersecurity: 40% of alerts are never investigated, while 61% of security teams admitted to ignoring alerts that later proved critical.

Organizations receive an average of 960 security alerts daily. Enterprises with over 20,000 employees see more than 3,000 alerts. The SANS 2025 SOC Survey confirms that 66% of teams cannot keep pace with incoming alert volumes.

Nearly 90% of SOCs are overwhelmed by backlogs and false positives. 80% of analysts report feeling consistently behind in their work.

Vectra's 2023 State of Threat Detection report found that SOC teams field an average of 4,484 alerts per day, with 67% ignored due to high false positives. Alarmingly, 71% of analysts believed their organization might already have been compromised without their knowledge, due to lack of visibility and confidence in threat detection capabilities.

In financial compliance, traditional transaction monitoring systems produce false positive rates of over 90% in some institutions. Fewer than 100 out of every 1,000 alerts are actionable.

When you ask humans to review thousands of decisions per day, you're not creating oversight. You're creating learned helplessness.

Skill Atrophy: The Use It or Lose It Problem

Here's the part regulators don't talk about: human-in-the-loop systems degrade the very skills humans need to intervene effectively.

A 2024 study warns that consistent engagement with an AI assistant leads to greater skill decrements than engagement with traditional automation systems. Why? Because AI takes over cognitive processes, leaving fewer opportunities to keep skills honed.

In aviation, the UK Civil Aviation Authority's Global Fatal Accident Review found that 62% of 205 accidents over 2002-2011 had flight crew related factors as the primary cause, potentially related to degraded manual handling skills.

Even the most trained operators on Earth drift out of manual proficiency when automation dominates.

Bainbridge's seminal work "The Ironies of Automation" identified that when operators monitor automation and intervene only when failure occurs, the net result is deterioration of manual skills due to lack of practice. The operator can find it difficult to maintain effective monitoring for more than half an hour when information is largely unchanged.

A 2025 study warns of the "out-of-the-loop" performance loss, where automation causes operators to lose situational awareness and manual skill over time. Automation bias is aggravated by task complexity, time pressure, high workload, and long periods of error-free automation operation which generate "learned carelessness."

You can't maintain expertise by validating someone else's work. You maintain it by doing the work.

The System Doesn't Converge

Georgetown's Center for Security and Emerging Technology concluded in their 2024 study that human-in-the-loop cannot prevent all accidents or errors. As AI systems have proliferated, so too have incidents where these systems have failed or erred, and human users have failed to correct or recognize these behaviors.

A 2022 case study titled "The Human in the Infinite Loop" found that human-AI loops often did not converge towards satisfactory results. The study revealed two key failures:

1. Optimization using preferential choices lacks mechanisms to deal with inconsistent and contradictory human judgments.

2. Machine outcomes influence future user inputs via heuristic biases and loss aversion.

The loop doesn't improve over time. It reinforces existing biases and creates new ones.

A 2024 study in Cognitive Research found that human judgment is significantly affected when participants receive incorrect algorithmic support, particularly when they receive it before providing their own judgment. In actual public sector implementations, system support is typically provided at the beginning of the decision process, where humans are given just a few options: validate or modify the system assessment.

This creates an anchoring effect that favors human compliance with the AI assessment.

The Regulatory Disconnect

A 2024 interdisciplinary study in Government Information Quarterly found that human oversight is seen as an effective means of quality control, including in the current AI Act, but the phenomenon of automation bias argues against this assumption.

The research concluded that excessive reliance may result in "a failure to meaningfully engage with the decision at hand, resulting in an inability to detect automation failures, and an overall deterioration in decision quality, potentially up to a net-negative impact of the decision support system."

Current EU and national legal frameworks are inadequate in addressing the risks of automation bias.

A 2025 analysis of algorithmic decision-making governance found that humans in "in the loop" governance functions provided "correct" oversight only about half the time. Lapses were primarily caused by human motivation to ensure compliance with their organization's goals rather than responsible AI principles.

Human oversight may be inadequate to regularly perform data quality duties.

The Alternative Architecture: Decision-Support, Not Decision-Review

Here's what I tell customers: the misconception is that AI will declare their product compliant. That's not what it does.

AI is a sophisticated pre-check. It helps discover gaps that would make the product noncompliant. That's a big difference.

The job of AI is to remove the tedious work of looking things up manually and cross-referencing across thousands of SKUs and documentation before subject matter experts deploy judgment. We shorten the path to expert judgment and authority.

We don't replace it.

A 2025 study on remote patient monitoring found that AI-integrated workflows with intelligent triage and clinical context help filter out unnecessary noise and focus provider attention where it's needed most. Critically, the research emphasized that clinical judgment remains essential and these tools are designed to support care teams rather than replace them.

The most effective systems offer transparency and flexibility, allowing clinicians to review alert histories, adjust thresholds, and override recommendations—ensuring AI remains a tool, not a decision-maker.

That's the architecture that works.

What Decision-Support Actually Looks Like

Take a food label review that must determine conformance with 21 CFR Part 101 here in the US. There's plenty of access to the regulatory corpus, warning letters issued against brands with labeling errors, and a near black-and-white interpretation of the regulation.

This makes a label evaluation with a well-constrained LLM near-deterministic.

But when there isn't a clear consensus in the industry, when the regulation itself remains open to interpretation and debate, when the enforcer is inconsistent, when the brand sees regulations as the floor or ceiling for quality and safety, and when there's limited access to examples—now it becomes murkier.

The LLM will do a good job collating the conflicting information. But tactics to ground its inferences are important, and how the results are presented is key.

We don't present the LLM's response as the mediator or arbitrator of the truth. We make it malleable enough and allow the subject matter expert to run what-if scenarios with the LLM.

What if the enforcer is more lenient? What if my company just issued a recall for this issue?

The LLM must be instructed to carry awareness of its confidence and lack of volatility in the results.

We run the inference in orders of magnitude that would be impractical for a human and present that value to the user as a confidence interval.

That's how you surface uncertainty that humans can't easily detect.

The UX Problem: How You Present Matters

Volume of decisions and overall UX determine whether humans over-rely on machines without proper due diligence.

At Signify, we open with potential issues. The same way a spellchecker highlights what's wrong with red wiggly lines.

The goal is to reduce, or at least manage, cognitive load as much as possible. For the most part, that's accomplished with thoughtful UX.

When you lead with issues rather than asking humans to verify everything looked right, you change the cognitive task. You're not asking for validation. You're asking for judgment.

That's the difference between decision-review and decision-support.

What Compliance Managers Actually Do

A compliance manager's job is not just to search, read, and match regulatory content. It's to deploy their judgment.

The longer it takes for the main function of their job to take place, the more onerous to the operation it becomes.

We're all in the service of taking products to market. Compliance sits on the critical path to do so.

The recurring aha moment teams have is when they see a compliance review performed in under 20 minutes at a negligible unit cost and compare it to how much an external attorney took and how much they charged—or if internally, when they realized the unlocked productivity their team can now achieve.

You're not just saving time. You're repositioning what compliance professionals actually do.

Moving them from search-and-match to judgment-and-strategy fundamentally changes their value to the organization.

The Speed Problem: Humans Can't Keep Up

A 2025 analysis found that the speed and volume of AI decisions overwhelm human capacity. In algorithmic trading, financial systems make thousands of micro-decisions per second, far beyond what any human could meaningfully monitor.

By the time humans recognize a problem, significant damage may already be done.

As AI becomes more deeply integrated into business processes, the number of decisions requiring review exponentially increases.

You can't solve a volume problem with a review process.

Thought Partner vs. Authority

When evaluating a new potential compliance use case for LLMs, I first consider whether the use case aims to use AI as a thought partner or an authority.

Why?

Because I'm wary of full delegation to any automated system to hold the key to the ultimate declaration of conformance.

Second, I look at the technical feasibility around data availability and the evaluations themselves.

That distinction between thought partner and authority shapes everything.

If you're asking AI to be the authority, you're building a decision-review system. You're asking humans to validate outputs after the fact.

That's where automation bias, alert fatigue, and skill atrophy converge to create failure.

If you're asking AI to be a thought partner, you're building a decision-support system. You're asking AI to surface information, run scenarios, and present confidence intervals so humans can deploy judgment.

That's where the architecture actually works.

What Happens When You Get It Wrong

When I discovered that fabricated CAS number, it forced us to establish deeper evaluations across the entire pipeline. It quickly showed where the LLM fails without the adequate ontology to guide the domain context.

That skepticism became productive. It forced us to build better systems.

But most organizations don't discover the fabrication until it's too late.

They discover it when a regulator flags it. When a customer gets harmed. When the system recommends something catastrophically wrong and a human, drowning in alerts and conditioned by months of accurate outputs, waves it through.

Human oversight doesn't work because humans aren't the problem.

The architecture is.

Decision-review systems ask humans to catch errors in a flood of confident recommendations. Decision-support systems ask AI to surface information so humans can make informed decisions.

One treats humans as validators. The other treats them as decision-makers.

Only one of those actually maintains human judgment.

And it's not the one regulators are mandating.

The information presented is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, regulatory, or professional advice. Organizations should consult with qualified legal and compliance professionals for guidance specific to their circumstances.

Human Oversight Doesn't Work: Why Most AI Compliance Systems Fail at the Point of Review

Human Oversight Doesn't Work: Why Most AI Compliance Systems Fail at the Point of Review

Feb 3, 2026